Identities in Contemporary European Cinema

The Role of Sound in The Scent of Green Papaya (Mui du du xanh)

Tran Anh Hung's delightful Scent of Green Papaya is notable for its virtual lack of dialogue. Through film, Tran demonstrates the power of sound as a narrative device. The near absence of communication between characters forces viewers to follow the film's plot by observing other cues, chief among these auditory signals. The film opens with Mui, a young servant girl, wandering through a scarcely lit town at night. As darkness envelops her face, the haunting sound of violins and a piano can be heard. The dissonance of the music creates a sense of unease, mirroring Mui's own anxiety at arriving at an unfamiliar place. Tran makes frequent use of this device, utilizing music to set the tone, throughout the film. Another notable example is when Mui meets the young son of her new mistress, Tin. Their antagonistic relationship is set to a playful melody, allowing the viewer to understand their interaction. In other scenes, whimsical traditional music is used to mirror Mui's fascination with the natural world. The shrill notes of a flute acompany her wide-eyed gaze as she watches as sap drips onto the ground, or observes an industrious ant carrying a large piece of food. The music allows the viewer to associate with Mui and helps to clarify her emotions given the absence of verbal cues.

Combining the use of diegetic and non-diegetic sounds, Tran is able to situate the film within a unique cultural context. The drone of a siren and the loud rumbling of an overhead aircraft are the only distinctive temporal markers in the film. Both sounds are non-diegetic and the viewer is left to infer their origins, concluding that the film must be set in French-occupied Vietnam. As the majority of the film is set in a household, these clues are important in establishing the setting of the film. Tran also relies on traditional Vietnamese music to convey the setting. The first half of the film is dominated by natural sounds, establishing the rural nature of the setting. Absent are the hustle and bustle of city life. From the first scene, the surprisingly loud chirp of crickets surrounds the viewer. In the second half of the film, this backdrop is largely supplanted by Khuyen's piano playing, indicating a shift from a traditional to a more Westernized setting. This is exemplified by the scene where Mui kicks around a high heel shoe. As she plays with the shoe, a piece of classical Western music replaces the buzz of crickets, indicating the shift in cultural landscapes.

Primarily a film about the everyday, Tran succeeds in depicting the sounds of everyday actions. From the sizzle of cooking vegetables to the gentle pitter-patter of Mui's bare feet as she walks through the home, Tran surrounds the viewer with noise, making the visual and auditory depictions of these actions synesthetic. For example as we watch her cut the papaya, we can hear the knife cut into the tense flesh, allowing us to see, hear and, to a certain extent, feel the papaya as Mui does, allowing the viewer to more deeply connect with the film. The Scent of Green Papaya demonstrates the importance of sound as a narrative technique through its masterful depiction of life in Vietnam.

Combining the use of diegetic and non-diegetic sounds, Tran is able to situate the film within a unique cultural context. The drone of a siren and the loud rumbling of an overhead aircraft are the only distinctive temporal markers in the film. Both sounds are non-diegetic and the viewer is left to infer their origins, concluding that the film must be set in French-occupied Vietnam. As the majority of the film is set in a household, these clues are important in establishing the setting of the film. Tran also relies on traditional Vietnamese music to convey the setting. The first half of the film is dominated by natural sounds, establishing the rural nature of the setting. Absent are the hustle and bustle of city life. From the first scene, the surprisingly loud chirp of crickets surrounds the viewer. In the second half of the film, this backdrop is largely supplanted by Khuyen's piano playing, indicating a shift from a traditional to a more Westernized setting. This is exemplified by the scene where Mui kicks around a high heel shoe. As she plays with the shoe, a piece of classical Western music replaces the buzz of crickets, indicating the shift in cultural landscapes.

Primarily a film about the everyday, Tran succeeds in depicting the sounds of everyday actions. From the sizzle of cooking vegetables to the gentle pitter-patter of Mui's bare feet as she walks through the home, Tran surrounds the viewer with noise, making the visual and auditory depictions of these actions synesthetic. For example as we watch her cut the papaya, we can hear the knife cut into the tense flesh, allowing us to see, hear and, to a certain extent, feel the papaya as Mui does, allowing the viewer to more deeply connect with the film. The Scent of Green Papaya demonstrates the importance of sound as a narrative technique through its masterful depiction of life in Vietnam.

Representations of Vietnamese Identity in Film

Film has often been used to convey the cultural and socio-political realities of a certain location. In this paper I will explore how film is used to depict Vietnamese identity in The Scent of Green Papaya, Indochine, and Daughter from Danang. Told from different perspectives, each film offers their own take on what constitutes Vietnamese identity.

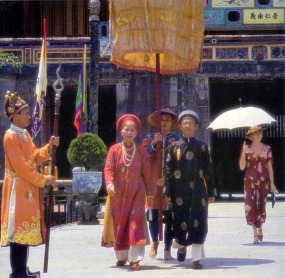

Directed by a Vietnamese immigrant to France, The Scent of Green Papaya depicts life in Vietnam during the French occupation. Its director, Tran Anh Hung, paints a portrait of traditional life using stunning visual imagery and a stirring sound track, composed of Vietnamese folk music. Tran depicts several aspects of Vietnamese culture from religion to food. He focuses the camera on Buddhist imagery throughout the film, highlighting its importance for the grandmother. Tran favors carefully-composed shots that chronicle even the minute details of everyday Vietnamese life. Through film, he paints a powerfu portrait of local customs. Through characterization he also attempts to expose the social stratification of Vietnamese society. Mui is carefully distinguished from Khuyen's wealthy fiancee, and, to a lesser extent, from the family that she serves revealing the divisions present in their society.

The other two films approach the issue of identity differently, defining Vietnamese culture by distinguishing it from Western culture. Indochine, an Academy Award-winning French production presents Vietnam as a backdrop for its primarily European protagonists. Catherine Deneuve's Mme Devries is the focus of much of the film. The owner of a large rubber plantation, Mme Devries employs several Vietnamese laborers. The Vietnamese characters of the film are depicted as either workers or dangerous radicals that need to be controlled. In one powerful scene, a Vietnamese family is killed by a French naval officer. When asked to justify his actions, he claims that they disrupted order by using Communist sayings. A small number of wealthy Vietnamese are also depicted, including Camille (Mme Devries' adopted daughter) and Tanh's mother (a wealthy merchant), once again revealing the social structure of Vietnamese society, highlighting the difference between the elites of pre-Communist Vietnam and the ordinary citizens of the country, partially explaining Tanh's own rejection of his background and embrace of socialist and communist ideologies.

In contrast with the two fictional films, the documentary Daughter from Danang uses actual footage of Vietnam to depict its cultural identity. Framed from the perspective of an Amerasian woman, Vietnamese culture is highly orientalized and depicted in opposition to the American culture that its protagonist, Heidi Bub, has come to embrace. Bub reacts like a tourist when she visits her birth mother's home. Her initial wonder evolves into a cultural misunderstanding when she decides not to send money to her mother. From the scene where her mother attempts to teach her how to say "I love you" to the scene where her brother explains her financial responsibility to her Vietnamese family, the film paints Vietnam as an exotic locale, with which the film's subject has little connection to, despite her blood ties. Heidi, who has had to deny and conceal her Asian background, has a very difficult time identifying with the culture of her homeland and the documentary, whether intentionally or not, exposes this, revealing the boundaries of transcultural exchange.

Through a variety of genres, from fiction to non-fiction, these films attempt to tackle the question of what exactly constitutes Vietnamese identity. Filmed from different perspectives, each adopts a unique approach coming to varying conclusions.

Directed by a Vietnamese immigrant to France, The Scent of Green Papaya depicts life in Vietnam during the French occupation. Its director, Tran Anh Hung, paints a portrait of traditional life using stunning visual imagery and a stirring sound track, composed of Vietnamese folk music. Tran depicts several aspects of Vietnamese culture from religion to food. He focuses the camera on Buddhist imagery throughout the film, highlighting its importance for the grandmother. Tran favors carefully-composed shots that chronicle even the minute details of everyday Vietnamese life. Through film, he paints a powerfu portrait of local customs. Through characterization he also attempts to expose the social stratification of Vietnamese society. Mui is carefully distinguished from Khuyen's wealthy fiancee, and, to a lesser extent, from the family that she serves revealing the divisions present in their society.

The other two films approach the issue of identity differently, defining Vietnamese culture by distinguishing it from Western culture. Indochine, an Academy Award-winning French production presents Vietnam as a backdrop for its primarily European protagonists. Catherine Deneuve's Mme Devries is the focus of much of the film. The owner of a large rubber plantation, Mme Devries employs several Vietnamese laborers. The Vietnamese characters of the film are depicted as either workers or dangerous radicals that need to be controlled. In one powerful scene, a Vietnamese family is killed by a French naval officer. When asked to justify his actions, he claims that they disrupted order by using Communist sayings. A small number of wealthy Vietnamese are also depicted, including Camille (Mme Devries' adopted daughter) and Tanh's mother (a wealthy merchant), once again revealing the social structure of Vietnamese society, highlighting the difference between the elites of pre-Communist Vietnam and the ordinary citizens of the country, partially explaining Tanh's own rejection of his background and embrace of socialist and communist ideologies.

In contrast with the two fictional films, the documentary Daughter from Danang uses actual footage of Vietnam to depict its cultural identity. Framed from the perspective of an Amerasian woman, Vietnamese culture is highly orientalized and depicted in opposition to the American culture that its protagonist, Heidi Bub, has come to embrace. Bub reacts like a tourist when she visits her birth mother's home. Her initial wonder evolves into a cultural misunderstanding when she decides not to send money to her mother. From the scene where her mother attempts to teach her how to say "I love you" to the scene where her brother explains her financial responsibility to her Vietnamese family, the film paints Vietnam as an exotic locale, with which the film's subject has little connection to, despite her blood ties. Heidi, who has had to deny and conceal her Asian background, has a very difficult time identifying with the culture of her homeland and the documentary, whether intentionally or not, exposes this, revealing the boundaries of transcultural exchange.

Through a variety of genres, from fiction to non-fiction, these films attempt to tackle the question of what exactly constitutes Vietnamese identity. Filmed from different perspectives, each adopts a unique approach coming to varying conclusions.

Film Analysis of Pedro Almodovar's Talk to Her (Hable con Ella)

It has often been said that real events are stranger than fiction. Seemingly adhering to this advice, Pedro Almodovar crafted his 2002 thriller Talk to Her after reading a news article about the real-life rape of a comatose patient. Talk to Her is a disturbing reflection on the themes of solitude and love set within the confines of a medical clinic. In an uncharacteristic turn for Almodovar, men, not women, are the focus of the film. Through the two male protagonists - the meticulous male nurse, Benigno, and the stoic Argentine journalist, Marco - Almodovar contrasts traditionally held conceptions of manliness with more radical ideas. This dualistic approach is pervasive throughout the film, with Almodovar intertwining the dual narratives, well preserving the essential contrast between the two.

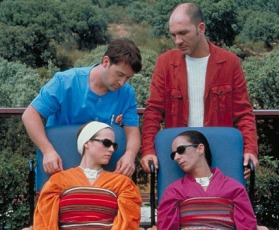

Like the other works of Almodovar, the film encorporates other artistic mediums to propel and enhance the narrative. From the haunting theatrical production of Cafe Muller and the bizarre silent film segment to more contemporary references, like the gossip show and bull-fighting scenes, Almodovar strengthens the artistry of his own craft by pointing to that of others. In fact, the film's opening scene occurs at the theater. The viewer is immediately introduced to the two male protagonists, Benigno and Marco, as they watch the performance intently, tears streaming down Marco's face. The scene immediately contrasts the reactions of the two men, establishing Almodovar's differentiation of the two. The next time we see Marco, he is clothed in blue scrubs caring for his supposed "girlfriend" Alicia. Benigno tenderly cares for Alicia, paying careful attention to every detail. He recounts, with passion, every detail of the performance as if to include her in his own life.

Almodovar introduces the second story line through another pop cultural reference. A television showing a gossip show is placed into the frame. A female presenter ruthlessly questions and confronts a young bull fighter, Lydia, about the nature of her relationship, revealing the potential vulnerability of such a superficially strong woman. Sensing this, Marco enters into a relationship with her, only to watch her get gored in the ring. It is then that the two stories are united at the hospital. Recognizing Marco, Beningno approaches him and strikes up what seems like an unlikely friendship with him. The two bond over their twin attentions to their respective females, with Benigno urging Marco to, as the title suggests, talk to Lydia.

Carefully manipulating time, Almodovar uses several flashbacks to flesh out the plot, revealing Benigno's obsessive nature. Exposing Benigno's solitude and questional sexuality, Almodovar paints Benigno as an obsessive, albeit harmless (as his name literally suggests in Spanish), stalker with no real ties to Alicia. Benigno's psychosis is further revealed when he delusionally states that his and Alicia's "relationship" is better than that of most couples and culminates in his implied rape of her. Benigno's intense focus and loving care of Alicia is contrasted throughout the film with Marco's brusquer approach to Lydia's care and his more spontaneous nature. A travel journalist, he frequently travels on a whim to write guide books.

Almodovar's tightly filmed sequences and carefully-crafted narration seem to mirror Benigno's own meticulous nature. The camera often lingers, such as when Lydia dresses for the bull fight or when Benigno bathes Alicia, lending the film an emotional sincerity as we the viewer are able to identify with the characters. The pacing of the film is also deliberately slowed, reflecting the theme of imprisonment (whether physical or emotional) allowing the viewer to savor the raw beauty of the film. Even the seemingly extraneous silent film segment pushes the plot along, highlighting the theme of male insecurity.

The film's emotionally wrenching conclusion, with the twin deaths of Lydia and Benigno and the "re-births" of Marco and Alicia, neatly ties the two plot lines, giving the film a sense of closure not often seen in the works of Almodovar. Yet even the final segment is framed from Marco's perspective. Almodovar's analysis could have, perhaps, been strengthened by the inclusion of a feminine point of view. The film, however, as the title suggests, merely talks to its woman, rather than with them.

Like the other works of Almodovar, the film encorporates other artistic mediums to propel and enhance the narrative. From the haunting theatrical production of Cafe Muller and the bizarre silent film segment to more contemporary references, like the gossip show and bull-fighting scenes, Almodovar strengthens the artistry of his own craft by pointing to that of others. In fact, the film's opening scene occurs at the theater. The viewer is immediately introduced to the two male protagonists, Benigno and Marco, as they watch the performance intently, tears streaming down Marco's face. The scene immediately contrasts the reactions of the two men, establishing Almodovar's differentiation of the two. The next time we see Marco, he is clothed in blue scrubs caring for his supposed "girlfriend" Alicia. Benigno tenderly cares for Alicia, paying careful attention to every detail. He recounts, with passion, every detail of the performance as if to include her in his own life.

Almodovar introduces the second story line through another pop cultural reference. A television showing a gossip show is placed into the frame. A female presenter ruthlessly questions and confronts a young bull fighter, Lydia, about the nature of her relationship, revealing the potential vulnerability of such a superficially strong woman. Sensing this, Marco enters into a relationship with her, only to watch her get gored in the ring. It is then that the two stories are united at the hospital. Recognizing Marco, Beningno approaches him and strikes up what seems like an unlikely friendship with him. The two bond over their twin attentions to their respective females, with Benigno urging Marco to, as the title suggests, talk to Lydia.

Carefully manipulating time, Almodovar uses several flashbacks to flesh out the plot, revealing Benigno's obsessive nature. Exposing Benigno's solitude and questional sexuality, Almodovar paints Benigno as an obsessive, albeit harmless (as his name literally suggests in Spanish), stalker with no real ties to Alicia. Benigno's psychosis is further revealed when he delusionally states that his and Alicia's "relationship" is better than that of most couples and culminates in his implied rape of her. Benigno's intense focus and loving care of Alicia is contrasted throughout the film with Marco's brusquer approach to Lydia's care and his more spontaneous nature. A travel journalist, he frequently travels on a whim to write guide books.

Almodovar's tightly filmed sequences and carefully-crafted narration seem to mirror Benigno's own meticulous nature. The camera often lingers, such as when Lydia dresses for the bull fight or when Benigno bathes Alicia, lending the film an emotional sincerity as we the viewer are able to identify with the characters. The pacing of the film is also deliberately slowed, reflecting the theme of imprisonment (whether physical or emotional) allowing the viewer to savor the raw beauty of the film. Even the seemingly extraneous silent film segment pushes the plot along, highlighting the theme of male insecurity.

The film's emotionally wrenching conclusion, with the twin deaths of Lydia and Benigno and the "re-births" of Marco and Alicia, neatly ties the two plot lines, giving the film a sense of closure not often seen in the works of Almodovar. Yet even the final segment is framed from Marco's perspective. Almodovar's analysis could have, perhaps, been strengthened by the inclusion of a feminine point of view. The film, however, as the title suggests, merely talks to its woman, rather than with them.