Born into Brothels

Zana Briski's Oscar-winning documentary, Born into Brothels: Calcutta's Red Light Kids, provides a shockingly intimate glimpse into the lives of the children of sex workers in Sonagachi, Calcutta's red light district. Briski, a photographer, uses her craft to communicate with the children and attempts to provide hope for the children and a distraction from the squalor in which they live.

The film is primarily composed of talking heads interviews with the children themselves mixed with still shots of the children's actual photography and upbeat music. It is through these interviews that the film truly shines. The viewer is struck by the honesty and maturity with which these extraordinary children discuss their lives. One young boy, Avajit, a talented photographer, sadly comments that "there is nothing called 'hope' in [his] future," while another shot features the image of a young girl meticulously scrubbing dishes juxtaposed with a shot of a woman in the background, possibly her mother, applies rouge. After wards the young girl acknowledges that she is aware of her mother's profession but prefers not to talk about it. For me, this was a startlingly mature response from such a young girl, which simultaneously saddened and inspired me. Briski relies on vignettes like these to tell the story in the first half of the film, which focuses almost exclusively on the children themselves. The second half, however, places Briski in front of the lens far too often, which for me was one of the major flaws of the film. By inserting herself into the narrative of the documentary, Briski draws the focus away from the children and places it on her own actions, practically screaming to the audience, "look at me!" While it is difficult to completely evade self-aggrandizement in altruistic films such as this one, Briski appears to enjoy the limelight a bit too much for my liking. Yet, despite these flaws, Born into Brothels is a visually stunning work that will tug on your heartstrings and is likely to remain with you for quite a while.

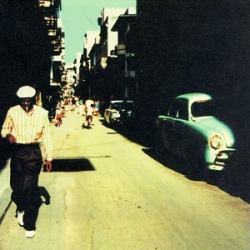

Buena Vista Social Club

Despite his subtle aggrandizement of Cooder, Wenders remains largely absent from the narrative of the film. Instead he allows the musicians to tell their own life stories. They speak openly to the camera, giving the viewer the sensation of talking with an older relative who is recounting tales of their glory days. Wenders allows the stories languish, following the natural course of speech, and they appear relatively unedited, lending an air of authenticity to the film. Set amongst bleak shots of a crumbling Havana, the musicians sport bright clothing and present a sense of 1950s vitality. Wenders often places voice-0vers over the scenes of Havana, conveying simultaneously the poverty and pride of a once-great nation. Given Cuba's fragile relations with the US, the film provides Americans with an interesting glimpse into a nation that is largely out of their reach. My favorite part of the film was the extensive concert footage, including a scene at Carnegie Hall in New York, which is arguably one of the most important scenes in the work.

The Gleaners and I (Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse)

It is often said that one man’s trash is another man’s treasure. Agnes Varda explores this cliché in her experimental documentary, The Gleaners and I. Through a series of interviews with various “gleaners” throughout France, who pick through leftovers, whether from a trash can or a field, Varda explores the role of gleaning within French society and attempts to reveal its social, political and cultural implications. She frames her analysis by categorizing the various types of gleaners, comparing the traditional gleaners with more modern varieties, including a chef, a group of hippy teenagers, and even a well-educated drifter. Through these brief impressions, the viewer is left with a powerful message concerning the role of social class in modern France. Varda contrasts artists who use trash to create interesting avant-garde pieces, some of which are world-renowned, with a drunk who is has lost virtually everything – his wife, children, job and even some of his teeth – and is forced to glean for his daily meals.

While gleaning appears to cut across socio-economic boundaries, it is immediately clear that not all gleaners are created equal. In one poignant scene, a group of gypsies distinguish themselves from a group of gleaners. In another, a woman distinguishes between “pickers” and “gleaners,” stating forcefully that she never gleans. These statements reveal not only the social stigma attached to gleaning, but also the division among gleaners themselves.

Varda’s interesting cinematography further serves to engage the viewer and to create a visual metaphor for the process of gleaning. The haphazard ways in which the scenes are arranged make Varda herself a glaneuse. She appears to pick and choose the subjects and locales she features, adding bizarre scenes of her own adventures in gleaning, from grabbing a broken clock to abstractly gleaning trucks from an auto route. By fashioning herself as a gleaner of sorts, Varda connects with her subject intimately. Despite the heavy nature of poverty, Varda approaches her topic with warmth and empathy. Her spectacular documentary inspires the viewer to meditate on the notion of what constitutes trash. I’m sure her imagery will remain with me next time I pass an open trash can.

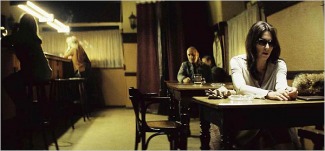

The Lives of Others (Das Leben der Anderen)

Winner of the 2006 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck's brilliant debut The Lives of Others tells the story of two very different men, Georg Dreyman, an idealistic writer, and Captain Wiesler, a staunch party official, who profoundly impact the lives of one another. Yet, the film clearly focuses on Wiesler's transformation, using the lives of Georg and Christa-Maria as a backdrop and catalyst fof his character evolution. Von Donnersmarck utilizes film as a narrative tool to explore the stark social and cultural realities of life in a socialist nation. Beautifully filmed scenes of orderly, gray Communist blocks dominate the film. One scene in particular features Wiesler driving home around a large empty roundabout at night, mirroring his own feelings of loneliness and isolation. Even his spartan apartment seems to reflect his predictable nature as a Socialist party lackey. It is only when he is assigned to spy on Dreyman that he truly comes alive. Alone in a dark room, Wiesel's face is highly emotive as he listens to the minutiae of Dreyman's life, providing an interesting foil to the personal responses of the viewer as they witness the same actions. As Wiesler becomes increasingly attached to Dreyman, he begins to intervene in his life. In one poignant scene, Wiesler rings the bell so that Dreyman is forced to witness his girlfriend's infidelity, calling into question the ethical limits of voyeurism. In this sense, the film is an intense psychological profile of Wiesler. Through his self-reflection, von Donnersmarck questions the role of party officials, leading viewers to consider the ethical implications of their actions. The cinematography further conveys this point. Every aspect of the film from the gray-scale and flat lighting of the shots to the slow pacing of the scenes seems to reflect the sense of oppression felt by the characters, reflecting the somber mood of the work as a whole. The sound track complements the visual aspects of the film, with Wiesler's moral dillema occuring as Dreyman plays a painfully beautiful piano sonata.

Narrative as a Formal System: Key Terms

story: the viewer’s imaginary construction of all the events in the narrative.

plot: all the events that are directly presented to us, including their causal relations, chronological order, duration, frequency, and spatial locations.

order: the aspect of temporal manipulation that involves the sequence in which the chronological events of the story are arranged in the plot.

duration: the aspect of temporal manipulation that involves the time span presented in the plot and assumed to operate in the story.

frequency: the aspect of temporal manipulation that involves the number of times any story event is shown in the plot.

narration: the process through which the plot conveys or withholds story information. The narration can be more or less restricted to character knowledge and more or less deep in presenting characters’ mental perceptions and thoughts.

Good Bye, Lenin!

Good Bye, Lenin! is steeped in GDR-era nostalgia, joining a growing movement in German society called 'ostalgie' (a combination of the German words for east and nostalgia). Yet, as reviewer Christina White of Cineaste points out, the film is "not guilty of glorifying the German Democratic Republic." Instead Becker's Alex creates an idealized version of an East Germany that never existed, what he describes as "the GDR I always wished for." In fact, the boundaries of history and the concept of recreating history are heavily explored throughout the movie. Becker combines actual news footage with Alex's recreated versions, situating the film within a rich historical context, notably one that has not been explored until recently. Alex uses powerful images of reunification, telling his mother that the excited emigrants are actually West Germans seeking refuge from capitalism, revealing the ease with which images can be manipulated and is perhaps a meditation by Becker on the role of propaganda within a centrally-planned state. The film is also punctuated with East German iconography, from the sky blue Trabant to an elusive jar of Spreewald pickles, which Becker cleverly uses to lend the film a sense of authenticity, validating his depiction of life in Berlin circa 1989.

The film succeeds most in its ability to incorporate comedy into a film about a relatively bleak period in German history. Becker carefully crafts the plot around Alex's recreation, offering continuous comic relief in an otherwise depressing film. Despite this, Becker's pacing tends to be slow, and I feel that his message could have been more effectively conveyed in a shorter film. As is, the story languishes, creating slight indifference on the part of the viewer as they watch Alex lie to his mother for the umpteenth time. That said, Good Bye, Lenin! is overall a spectacular film that is at once heartwarming and hilarious.

Daughter from Danang

At the beginning of the film, the director combines voice-overs from Bub with that of her birth mother, presenting a balanced version of Bub's adoption. The cutting back and forth provides an objective version of the events, avoding glorifying Bub or villainizing her birth mother. The director is essentially telling Bub's story, but deliberately chooses to explore the story from a variety of perspectives, including that of her birth mother and that of a journalist.

The film carefully presents the cultural situation of Bub, essentially an American, as she desperately tries to reconnect with her Vietnamese heritage. Traditional Vietnamese music provides the backdrop for much of the film, effectually situating the narrative within a specific cultural context. Alternating between sorrowful and joyful, the music attempts to reflect Bub's often-difficult attempt to identify with Vietnamese culture. One scene shows Bub's birth mother teaching her how to say "I love you" in Vietnamese, with Bub butchering the words with her heavy Southern drawl. Scenes like this attempt to explain the delicate situation adopted children face, torn between different cultures. The film also presents a critical examination of racism in the United States. One scene that struck me was where Bub's aunt told the camera about how Bub had to repeat a grade because "she no speak the English good," revealing the lingering of racist sentiments in the post-segregation South.

Paris, je t'aime

While the film does lack a central plot, the use of similar cinematographic techniques helps to unify the work as a whole. The use of color is particularly brilliant, complementing several scenes. In Vincenzo Natali’s “Quartier de la Madeleine,” for example, the scene is shot mostly in black and white, save for the deep red of the blood that comes to symbolize the bond between the two. Similarly the “Bastille” scene features a woman in a bright red trench coat, which is contrasted sharply with her usually drab wardrobe, and signaled as the reason that her husband initially fell in love with her. The use of color extends to the postcard-perfect scenes of Paris that are used as the glue which connects the individual segments.

The sheer number of different directors allows for a huge variance in cinematic styles. Gus Van Sant’s “Marais” segment uses carefully-filmed shots reminiscent of New Wave auteur Jean-Luc Godard as the camera only focuses on the young French man as he speaks. Several other innovative shots are included in other segments, from Alfonso Cuaron’s “Parc Monceau,” which is composed of one long take, to Chrstopher Doyle’s misguided “Porte de Choisy,” which combines sleek special effects with martial arts. The film’s hodge-podge of cinematic styles mirrors the similarly fragmented culture of modern Paris. Several segments attempt to explore the cultural realities of life in Paris, from immigrant culture (Walter Salles’ “Loin du 16eme,” Oliver Schmitz’s “Place des Fetes,” Gurinder Chandha’s “Quais de Seine,” and Christopher Doyle’s “Porte de Choisy”) to drug use (Olivier Assayas’ “Quartier des Enfants Rouges”).

Alexander Payne’s delightfully simple final segment offers the perfect conclusion to the film. The story of a lonely middle-aged woman who finds an unlikely love in Paris, the city itself, Payne’s “14eme arrondissement” represents the unifying theme of the entire film. Ultimately Paris, je t’aime presents a beautiful postcard-view of life in Paris without ever exposing its soul, which is enough to leave any viewer wanting more.

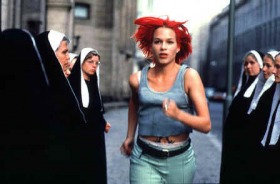

Run Lola Run (Lola rennt)

Twyker draws the viewers attention to the action of the film with a brilliant combination of color and sound effects. Brilliant reds reoccur throughout the work, from Lola's fiery hair to the red overtones of the scenes of Lola and Manni in bed which connect the alternative segments. Red is also the color of the ambulance which plays a huge role in the conclusions of the various segments. Red, a warm color, advances from the screen, and offers a sharp contrast from the cool blues and greys of Twyker's Berlin. The same effect is apparent in the running sequences, where Lola's hair attracts the viewers' gaze. The addition of high-tempo music during these scenes heightens the viewers interests and lends the scenes a sense of urgency, emphasizing the film's rapid pace. Interestingly, at the end of the first sequence, Zwyker uses slow-paced music as Manni and Lola flee. The music highlights the scene, as the music becomes disassociated from the on-screen action for the first time, foreshadowing Lola's impending death.

As Kate Matthews observes, in her article Running in Circles, "the defining feature of Lola's narrative structure is its treatment of time." I completely agree. Twyker manipulates time, resulting in what Matthews labels a "multiform" plot. The film establishes the initial plot conflict in a brief introduction before plunging into the three action segments, which each present the ways in which the next twenty minutes of Lola's life could play out. This attention to the subjunctive, what could be, forces viewers to focus on even the smallest details, which would usually be regarded as inconsequential. There are no random coincidences in the film, even the smallest actors contribute to Lola's fate. The film's central theme, then, seems to be the power of chance. In each segment, with the exception of the first, Lola escapes catastrophe by luck.

Run Lola Run is an artistic meditation on the role of time and chance. Using innovative filmic techniques, Twyker attempts to expose the importance of luck and chance to our daily lives. From now on I plan to pay closer attention to seemingly random people and events, keeping in mind the interconnected nature of our world.

L'Auberge espagnole

Cedric Klapisch's L'Auberge espagnole is the "true" story of seven Europeans living in an apartment, what reviewer A.O. Scott labels the "Real World: Catalonia." Like a reality show, this film focuses on the experience of Xavier and his flat-mates as they discover Barcelona as part of the ERASMUS program.

Klapish succeeds in exploring the numerous relationships of the roommates, in particular that of lesbian Isabelle, yet he fails to truly round out any of his characters. Even Xavier, the film's narrator and main character, is poorly developed. The viewer is left with a vague impression of his motivation, the prospect of a bureucratic job if he improves his Spanish, and little more. His affair with Anne-Sophie is similarly vague, and seems completely devoid of passion. Even the break-up with Martine elicits little symapthy for Xavier, whom Scott describes as "not entirely likeable." The other characters primarily serve as a backdrop for Xavier's life. Indeed, serious sub-plots like the surprise arrival of Wendy's boyfriend when she is in bed with her American fling and the equally surprising revelation that Lars is a father go undeveloped. In the case of the latter, Soledad briefly chastizes Lars about his lack of emotion before the sub-plot disappears entirely.

Where Klapisch's film fails in terms of characterization it succeeds thematically. The chaos of the apartment and the clash of cultures mirror the ongoing integration of Europe as the EU continues to mature. The film frequently switches languages, presenting the viewer with a realistic view of multi-cultural Europe. The blurred and segmented shots seem to further exemplify this difficult transition. The irony of the film lies in the fact that Xavier immediately becomes disillusioned with his ministry job, yet his drive to attain it initially led him to Barcelona which taught him the life lessons necessary for his new career as a writer.

L'Auberge espagnole offers viewers an entertaining trip through Postmodern Europe. The film's idyllic shots of Barcelona provide the perfect backdrop for the escapades of Xavier and his roommates. Sadly, like a reality show, the film only presents a superficial view of its characters, never going deeper.

11'9"01: onze minutes, neuf secondes, un cadre

Alain Brigand's compilation, 11'9"01, overloads the senses with nine emotionally-charged shorts depicting the world-wide response to the tragedy of September 11. Combining the work of nine international directors, the film presents a wide variety of opinions ranging from the sympathetic to the bitter. Viewers expecting a commemoration will likely be disappointed, as the film discards kid gloves and instead approaching the tragedy with an emotional honesty that is at once shockingly refreshing. From Samira Makhmalbaf's insightful reflection on the childhood innocence to Shohei Imamura's disturbing allegorical meditation on pacifism, Brigand's film often confronts viewers with scenes that are difficult, if not painful, to watch.

The shorts are supposedly interconnected by their treatment of the attacks on Washington and New York, but this link is tenuous at best. In Makhmalbaf's the attacks are referenced explicitly by the extremely powerful image of a smoking chimney, but the tie is less clear in Imamura's seemingly inane piece. The story of a Japanese soldier who returned from World War II believing he was a snake, Imamura's piece seems out of place at first glance. However, the powerful last shot, a snake proclaiming that "there are no holy wars," clarifies the link, providing a powerful statement regarding the destructive nature of religion in our world.

Sean Penn's segment is similarly allegorical, telling the story of a lonely old man in New York. Penn uses dynamic shots to establish the daily routine of its old protagonist, including his daily talks with his absent wife, who is presumably deceased. The old man has an epiphany, however, as the towers fall, finally coming to the conclusion that his wife is dead and, as Burr writes, "joins the world of the living." Penn's segment can thus be seen as a reflection of the national wake-up call spurred by 9/11.

While there were a few extremely insightful segments, in my opinion, the vast majority fell flat. Eleven minutes is really too long for a short film, and several of the segments seemed to fare for the worse because of it. Others were simply misguided. While Ken Loach's segment featured stunning, and saddening, footage from the September 11, 1973 Chilean coup d'etat, it failed to fully connect with the theme of the compilation. Its self-righteous narrator is too stuck in the past to address the present. While Mira Nair's segment suffers from poor acting and a similarly self-centered narrative.

Shining at times, Brigand's 11'9"01 largely fails to do justice to its themes or even its director. Perhaps it was made too soon after the attacks of 9/11 to truly be self-reflective. Either way, I would urge any potential viewer to think carefully before seeing this film. If approached with the right attitude, one will leave having learned something. But overall, many Americans will just leave disappointed.

Le Fabuleux Destin d'Amelie Poulain

Jean-Pierre Jeunet's 2001 Amelie takes viewers on a whimsical tour of Paris through the eyes of its wide-eyed protagonist, the somewhat quirky Amelie Poulain. A young waitress living alone in Montmartre, Amelie lives a lonely life until she discovers a box hidden in her bathroom full of relics from a past tenant. After returning the box, Amelie decides to perform a series of good deeds, profoundly impacting the lives of those around her, and even resulting in her own romantic encounter. A bit long at 2 hours, Amelie is, overall, an entertaining film with a warm-hearted message, urging viewers to help those around them.

Jeunet introduces us to a cast of highly memorable characters. Using omniscient narration, he fills us in on even the most minute details of each character, at times reading like a bad personal ad. We are confronted, from the beginning, with the strange upbringing of Amelie, from her mother's tragic yet bizarre death to her father's equally bizarre devotion to creating a kitschy shrine for her. This intense characterization helps the viewer to connect with Amelie immediately and to understand her character's motivations a little better, as her actions themselves are often harder to identify with (for example, her elaborate scheme to return the album to Nino).

The entire film has a fantasy-like feel to it. From the rich, warm colors to fanciful shots of paintings talking, Amelie seems to be set in a dream world version of Montmartre, rather than the real thing. The exaggerated quirkiness of many of the characters, particularly Georgette, seems to further enhance the surreal quality of the film in general. However, at times Jeunet's focus on details can become overwhelming. As reviewer Elvis Mitchell of The New York Times observes, the film "has what could be called meticulous clutter, a placement of imagery that covers every square centimeter of the screen."

The saccharine story of Amelie certainly delights, but may leave some viewers with a tooth-ache. The central love story left me slightly confused an underwhelmed, yet will appeal to many. It is the film's exploration of social relations and the impact of good deeds that offers the film a sense of universality, perhaps explaining its global success, particularly in the US, where European films are often poor box office performers.

Russian Dolls (Les Poupees russes)

The sequel to Cedric Klapisch's successful L'Auberge espagnol, 2005's Russian Dolls eschews the original's treatment of European multiculturalism in order to focus on the diversity of protagonist Xavier's bedroom. A superficial portrait of Xavier's womanizing, Russian Dolls lacks the depth and emotion of its predecessor. And although Xavier's relationships with the characters from the 2002 film are further explored, we are still left with little to no idea of who most of them really are. In this sense, Russian Dolls could aptly be called "The Xavier Show."

The film takes place 5 years after L'Auberge espagnole left off. A self-proclaimed bachelor, Xavier leads a vapid life consisting of writing screenplays for a trashy soap opera and having a string of one-night stands with a number of women who seem to have as little interest in him as he has for them. This shallow existence is punctuated with somewhat awkward visits with his ex Martine, who is now a single mother. Yet, despite Martine's increased screen time, we learn surprisingly little about their seemingly complex relationship. This seems to be a common thread in the film, with Klapisch frequently introducing somewhat interesting story-lines before discarding them without warning. For example, he briefly touches on the racial diversity of Paris by introducing Kassia, an alarmingly beautiful sales clerk with a Senegalese background, before discarding her after a shallow sex scene. The same is done with Spanish beauty Neus, shown in flashbacks, and British model Celia, who admittedly receives slightly more screen time. In fact, the only character other than Xavier that Klapisch attempts to develop is Brit Wendy, who is defined through brief treatments of her rocky former relationship and her familial issues.

What the film lacks in characterization, it makes up with beautiful cinematography. Klapisch experiments openly with filmic techniques, framing his story within a non-linear format. Other techniques, from the manipulation of time and speed to the inclusion of fantasy sequences add a whimsical feel, making the film a visual treat. Beautiful shots of Paris, London and St. Petersburg serve as the perfect backdrop for the film's equally beautiful cast. One scene in particular features the nearly flawless Celia strutting down a perfectly-proportioned Russian street, complementing Xavier's meditation on the flaws of perfection and the superficiality of beauty. Sadly, however, Klapisch fails to recognize the superficilaity of his own narrative.

Like L'Auberge espagnole, Russian Dolls is an enjoyable film lacking in substance. While the film succeeds in documenting 20-something Euro Chic, leaving viewers emulating Xavier's fast-paced life, it fails to truly address the social complexities of life in a modern, rapidly-changing Europe.

Salut Cousin!

Salut Cousin! attempts to defy cultural stereotypes of Maghrebi immigrants, presenting a cast of largely well-mannered Algerians and a sterilized version of the drab housing projects of the banlieue. The violence and the grit of the projects is nearly absent from the film, except for in the imaginative mind of Mok. Fashioning himself as a rapper of sorts, Mok angrily tells Alilo of his difficult life in the projects, painting an exaggerated story of misfortune and violence, illustrating the ridiculousness of the stereotypical images of banlieu life. In reality, Mok's family is comfortably middle-class, with his mother's chief concern being her weight, rather than her safety. And despite Mok's best attempts to portray himself as a serious rapper, the sad reality is that his rhymes come not from the slums, but from the childrens fables of Jean La Fontaine. However, Allouache does not only rely on humor, also making serious points. In one scene, a young African girl in a phone booth is threatened by a group of French men, illustrating the prejudice present in some Parisian neighborhoods.

Sadly, however, Salut Cousin!'s comedic nature renders its social commentary less powerful to an audience that has witnessed the 2005 riots. Media images of homogeneous concrete housing projects and burning cars seem to reinforce the same stereotypical images of banlieue life that Allouache attempted to overturn in 1996. Allouache's rudimentary cinematography makes the film look outdated, with the picture quality more reminiscent of a made-for-TV movie from the 1980s. A lighthearted comedy, Salut Cousin! skirts many of the social issues it wishes to expose, rendering its sterilized image of Parisian immigrant culture less powerful.

The Girl in the Cafe

David Yates' saccharine romantic comedy The Girl in the Cafe is like a good cup of English tea with perhaps one too many spoonfuls of sugar. Written by Richard Curtis, who is best known for the feature films Notting Hill and Love, Actually, this made-for-television film tells a cliche boy meets girl story set to the background of a fictionalized G8 Summit in Iceland. Bill Nighy plays Lawrence, a staid British diplomat, who meets a mysterious Scottish lassie (Gina, played by Kelly Macdonald) in a cafe and strikes up an unlikely romance with her. What Lawrence does not, and cannot now, is that Gina has a tarnished past and a strong opinion on global policy as far as aid for impoverished nations is concerned. The Girl in the Cafe plays like a slightly intellectual version of a Lifetime movie. The romantic aspects are predictable with a dash of do-gooder enthusiasm and a mild message concerning foreign aid thrown in.

The opening scene features the bland Lawrence walking down a rainy London street amid a barrage of black umbrellas, symbolizing perhaps the monotony of his daily routine. A stirring melody plays, lending the scene a somber tone. Once in the cafe, Lawrence spies Gina, a somewhat mousy girl. Silhouetted in yellow lights, the scene sets up a later scene where a "scrubbed-up" Gina wows Lawrence. The film addresses Gina and Lawrence's budding romance with a sensitivity that almost allows the viewer to dismiss the glaring age difference between the two. Yet Yates' superb direction leaves us cheering for their lives, hoping it will all work out. The awkward dialogue and slow pacing force the viewer to watch the film closely, searching for even the subtlest clues, even when the scenes are painfully embarrassing to watch.

The cinematography of the film is superb and far surpasses the viewer's expectations for a television production. Visually stunning shots of the raw beauty of Reykjavik complement Lawrence and Gina's growing connection. The sensible Scandinavian decor provides the perfect backdrop for one of the most awkward, albeit tender, sex scenes I have ever witnessed. That said, the romantic side of the film is perhaps the best thematic component. The films other thematic approach addresses the issue of political activism and the responsibility of the world's leading economies to promote positive change. In one particularly poignant scene, a groggy Lawrence enters the living room of his hotel suite only to find Gina reading his briefing material. Gina suggests that they add pictures of global suffering to emphasize the need for activism. Ironically, as reviewer Alessandra Stanley points out, "Gina chides bureaucrats for not seeing African women and children as people who deserve to be treated with the same compassion as their own wives and daughters, yet those suffering people remain an unseen abstraction in this film as well."

The Girl in the Cafe is an enjoyable ninety-minute distraction best left for a rainy London day. While the film offers beautiful cinematography and excellent performances by Mr. Nighy and Ms. Macdonald, it fails to truly offer any substance. Its feel-good message falls short in that it is as shallow as the approach of the bureaucrats that Gina berates.